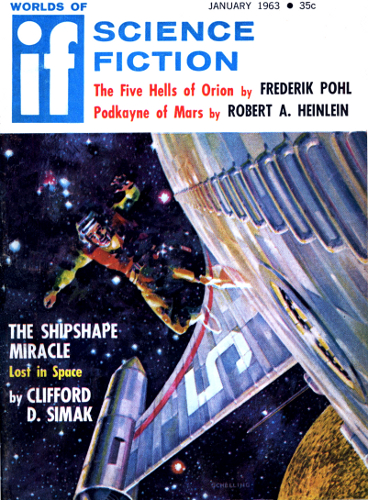

THE FIVE HELLS OF ORION

BY FREDERICK POHL

Out in the great gas cloud of the Orion

Nebula McCray found an ally—and a foe!

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Worlds of If Science Fiction, January 1963.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

His name was Herrell McCray and he was scared.

As best he could tell, he was in a sort of room no bigger than a prisoncell. Perhaps it was a prison cell. Whatever it was, he had no businessin it; for five minutes before he had been spaceborne, on the Long Jumpfrom Earth to the thriving colonies circling Betelgeuse Nine. McCraywas ship's navigator, plotting course corrections—not that there wereany, ever; but the reason there were none was that the check-sightingswere made every hour of the long flight. He had read off the azimuthangles from the computer sights, automatically locked on their beaconstars, and found them correct; then out of long habit confirmed thelocking mechanism visually. It was only a personal quaintness; he haddone it a thousand times. And while he was looking at Betelgeuse, Rigeland Saiph ... it happened.

The room was totally dark, and it seemed to be furnished with acollection of hard, sharp, sticky and knobby objects of various shapesand a number of inconvenient sizes. McCray tripped over somethingthat rocked under his feet and fell against something that clatteredhollowly. He picked himself up, braced against something that smelleddangerously of halogen compounds, and scratched his shoulder, rightthrough his space-tunic, against something that vibrated as he touchedit.

McCray had no idea where he was, and no way to find out.

Not only was he in darkness, but in utter silence as well. No. Notquite utter silence.

Somewhere, just at the threshold of his senses, there was somethinglike a voice. He could not quite hear it, but it was there. He sat asstill as he could, listening; it remained elusive.

Probably it was only an illusion.

But the room itself was hard fact. McCray swore violently and out loud.

It was crazy and impossible. There simply was no way for him to getfrom a warm, bright navigator's cubicle on Starship Jodrell Bank tothis damned, dark, dismal hole of a place where everything was out tohurt him and nothing explained what was going on. He cried aloud inexasperation: "If I could only see!"

He tripped and fell against something that was soft, slimy and, likebaker's dough, not at all resilient.

A flickering halo of pinkish light appeared. He sat up, startled. Hewas looking at something that resembled a suit of medieval armor.

It was, he saw in a moment, not armor but a spacesuit. But what was thelight? And what were these other things in the room?

Wherever he looked, the light danced along with his eyes. It was likehaving tunnel vision or wearing blinders. He could see what he waslooking at, but he could see nothing else. And the things he couldsee made no sense. A spacesuit, yes; he knew that he could constructa logical explanation for that with no trouble—maybe a subspacemeteorite striking the Jodrell Bank, an explosion, himself knockedout, brought here in a suit ... well, it was an explanation with moreholes than fabric, like a fisherman's net, but at least it was rational.

How to explain a set of Gibbon's Decline and Fall of the RomanEmpire? A space-ax? Or the old-fashioned child's rocking-chair, thechemistry set—or, most of