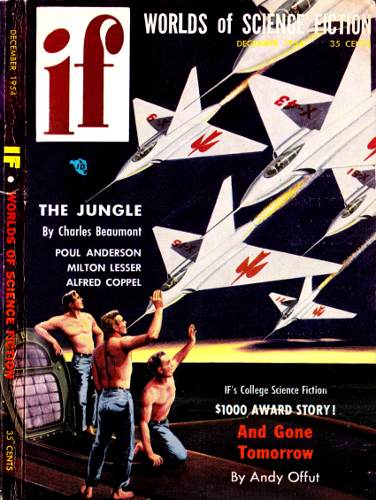

A Cold Night for Crying

BY MILTON LESSER

It's much easier to believe than

disbelieve, whether it's a truth or

an untruth, when you have to. And

when the brain and body are weak ...

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Worlds of If Science Fiction, December 1954.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

The snow sifted silently down, clouds of white confetti in the glare ofthe street lamps, mantling the streets with white, spilling softly fromladen, wind-stirred branches, drifting with the wind and embanking thescars and stumps of buildings that remained of what had been the city.

Mr. Friedlander trudged across the wide, quiet avenues, his bare,balding head burrowed low in his tattered collar for warmth, chinagainst chest, wet feet numb and stinging with cold inside his tornovershoes which could not be replaced until next winter, and then onlyif the Karadi did not decrease the clothing ration still further.

All the way home, he conjured fantasies from the white, multi-shapedexhalations of his breath. Here it was the smoke of a goodHavana-rolled cigar and there the warm hissing steam from a radiatorvalve and later the magic-carpet clouds from the funnel of an oceanliner that might take him to far, warm places the Karadi had notreached. Almost, he thought he heard the great sonorous drone of theship's whistle, but it was the toot of an automobile horn as thesleek vehicle came skidding around a corner, almost running down Mr.Friedlander before it disappeared in the swirling flurries of snow. Hethought if he followed the tire tracks before the snow could cover themhe would discover in which section of the city these particular Karadilived, but he shook his fist instead, knowing the gesture would bring,at worst, a reprimand.

In the dim hallway of his tenement, smelling pungently of cabbage andturnips—and from somewhere way in back the faint, unmistakable aromaof beef—Mr. Friedlander shook the snow from his coat and stamped hisnumb feet before he climbed the three dark flights to his apartment. Ateach landing he would pause and look with longing and resentment at thedoor of the unused elevator shaft, then shrug and wonder why the Karadihad denied man even this simple luxury.

On the floor below his own, Mr. Friedlander heard the unmistakablecrackling sound of a short-wave radio receiver. The fools! He wasn'tgoing to talk, he lost no love on the Karadi. But there were others.There were neighbors, friends, brothers, even wives, there were theobvious quislings you shunned and the less obvious ones you didn'tsuspect until it was too late. One thing you never did was listento the short-wave radio so defiantly its crackling could be heardnot merely on the other side of the door but all the way out on thelanding. The punishment was death.

Mr. Friedlander paused in front of his own door, where the odor ofstrong yellow turnips assailed his nostrils. It was so unsatisfyinglyfamiliar, he almost gagged. The new generation hardly remembered thedelightful old foods, but if Mr. Friedlander shut his eyes and thought,he could clearly smell steak and roast chicken and broiled lobsterswimming in butter and a dry red wine to wash everything down slowly,so slowly he could taste every tiny morsel.

He pushed